This man survived Hiroshima bombing – and has a stark warning for us all

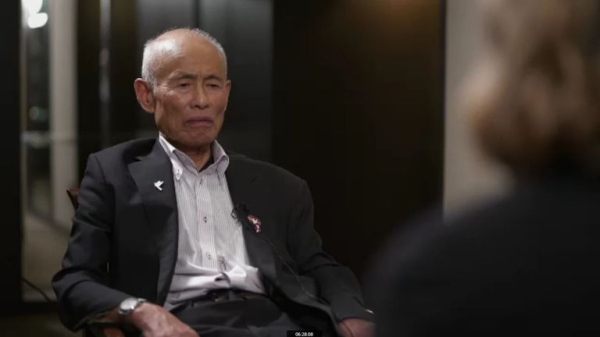

Toshiyuki Mimaki is exhausted when we meet him.

The 83-year-old sinks into his chair, closes his eyes, and asks us to keep it brief.

But then he starts talking, and his age seems to melt away with the power of his stories.

He is a survivor of Hiroshima’s atomic bomb, a lifelong advocate for nuclear disarmament and, as of last year, a Nobel Peace Prize winner.

But now, on the 80th anniversary of the bombing, he comes with more than just memories – he has a message, and it is stark.

“Right now is the most dangerous era,” he says.

“Russia might use it [a nuclear weapon], North Korea might use it, China might use it.

“And President Trump – he’s just a huge mess.

“We’ve been appealing and appealing, for a world without war or nuclear weapons – but they’re not listening.”

‘I didn’t hear a sound’

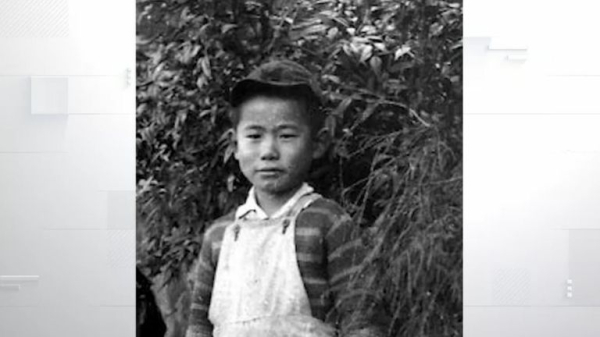

Mr Mimaki was three years old when the US dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima.

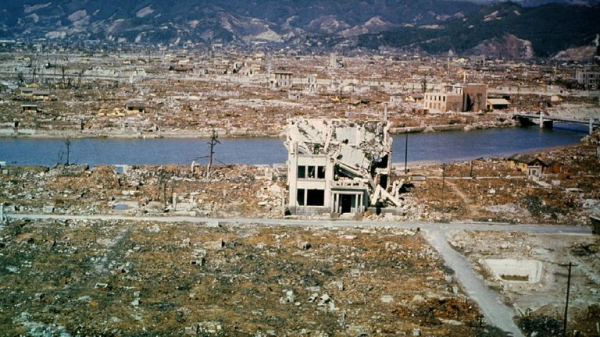

It was the first time a nuclear weapon had been used in war, and it’s remembered as one of the most horrific events in the history of conflict.

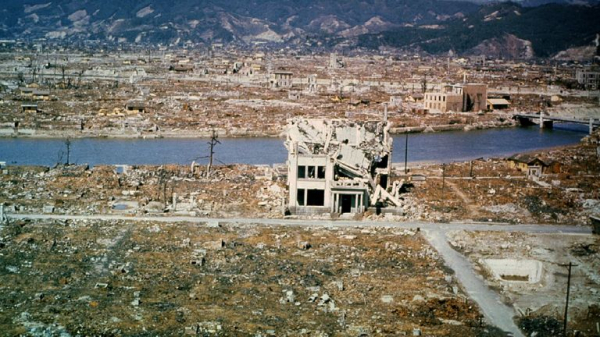

It’s estimated to have killed over 70,000 people on the spot, one in every five residents, unleashing a ground heat of around 4,000C, melting everything in its path and flattening two thirds of the city.

Horrifying stories trickled out slowly, of blackened corpses and skin hanging off the victims like rags.

“What I remember is that day I was playing outside and there was a flash,” Mr Mimaki recalls.

“We were 17km away from the hypocentre. I didn’t hear a bang, I didn’t hear a sound, but I thought it was lightening.

“Then it was afternoon and people started coming out in droves. Some with their hair all in mess, clothes ragged, some wearing shoes, some not wearing shoes, and asking for water.”

‘The city was no longer there’

For four days, his father did not return home from work in the city centre. He describes with emotion the journey taken by his mother, with him and his younger bother in tow, to try to find him.

There was only so far in they could travel, the destruction was simply too great.

“My father came home on the fourth day,” he says.

“He was in the basement [at his place of work]. He was changing into his work clothes. That’s how he survived.

“When he came up to ground level, the city of Hiroshima was no longer there.”

‘People are still suffering’

Three days later, the US would drop another atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki, bringing about an unconditional Japanese surrender and the end of the Second World War.

By the end of 1945, the death toll from both cities would have risen to an estimated 210,000 and to this day it is not known exactly how many lost their lives in the following years to cancers and other side effects.

“It’s still happening, even now. People are still suffering from radiation, they are in the hospital,” Mr Mimaki says.

“It’s very easy to get cancer, I might even get cancer, that’s what I’m worried about now.”

Tragically, many caught up in the bomb lived with the stigma for most of their lives. Misunderstandings about the impact of radiation meant they were often shunned and rejected for jobs or as a partner in marriage.

Many therefore tried to hide their status as Hibakusha (a person affected by the atomic bombs) and now, in older age, are finding it hard to claim the financial support they are entitled to.

And then there is the enormous psychological scars, the PTSD and the lifelong mental health problems. Many Hibakusha chose to never talk about what they saw that day and live with the guilt that they survived.

For Mr Mimaki, it’s there when he recounts a story of how he and another young girl about his age became sick with what he now believes was radiation poisoning.

“She died, and I survived,” he says with a heavy sigh and strain in his eyes.

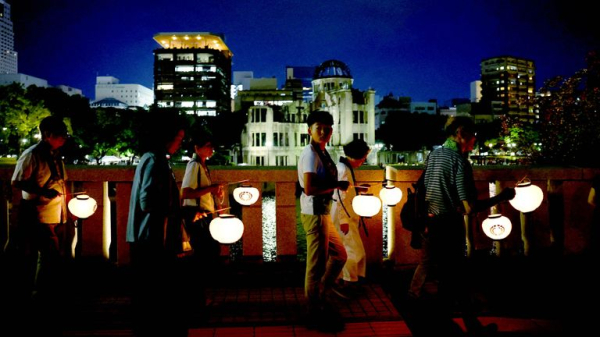

He has subsequently dedicated his life to advocacy, and is co-chair of a group of atomic bomb survivors called Nihon Hidankyo. Its members were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2024.

‘Why do humans like war so much?’

But he doesn’t dwell much on any pride he might feel. He knows it’s not long until the bomb fades from living memory, and he deeply fears what that might mean in a world that looks more turbulent now than it has in decades.

Indeed, despite advocacy like his, there are still around 12,000 nuclear warheads in the world in the hands of nine countries.

“In the future, you never know when they might use it. Russia-Ukraine, Israel-Gaza, Israel-Iran – there is always a war going on somewhere,” he says.

“Why do these animals called humans like war so much?

“We keep saying it, we keep telling them, but it’s not getting through, for 80 years no-one has listened.

“We are Hibakusha, my message is we must never create Hibakusha again.”